PostgreSQL Table Partitioning Primary Keys — The Reckoning — Part 2 of 2

In Part 2 of this 2 part PostgreSQL 🐘 Table Partitioning series, we’ll focus on how we modified the Primary Key online for a large partitioned table. This is a disruptive operation, so we had to use some tricks to pull this off.

Read on to learn more.

If you haven’t already read Part 1 of this series, please first read PostgreSQL Table Partitioning — Growing the Practice — Part 1 of 2 which describes why and how this table was converted to a partitioned table.

The context there will help explain the circumstances we were operating from.

Outline

- Write locks and partitioned tables

- The original Primary Key strategy used

- The problem with that strategy

- The SQL Solution

- Wrap Up

Original Context: Database and Table

- PostgreSQL 13

- Declarative partitioning with

RANGEtype - Table writes behavior is “Append Mostly”

- New writes at a rate of around 10-15 rows/second

- 75+ partitions, table size is 500 GB and contains around 1 billion rows

- Primary Key constraint on child partitions on

idcolumn - No Primary Key constraint on parent

- Partition key column is

created_attimestamp

Partitioned Table Primary Keys

In the earlier post, we discussed why and how we conducted on online table partition conversion.

In that design, we’d set up a PRIMARY KEY constraint on each child partition, but none on the parent. This met the needs of the application.

Each child partition Primary Key was on the id column only. PostgreSQL allows the child table to have a Primary Key constraint with none defined on the parent, but not the other way around.

Further, PostgreSQL prevents adding a Primary Key on the parent that conflicts with the child. 1

When we decided on the Primary Key and Unique Indexes structure for the table, the needs of the application and conventions of pgslice drove the decision. We didn’t have a need for a Primary Key on the parent table.

We found out later this was short sighted, and in fact we did have a need for a parent table primary key.

The need for this was outside the application, but for an important consumer, our data pipeline process that detects row modifications and copies them to our data warehouse.

What happened with the data pipeline?

The Reckoning

An engineer noticed an excessive amount of queries in the data warehouse since we’d partitioned the table.

The data warehouse was attempting to identify the new and changed rows, but it had become inefficient to do so without a Primary Key on the parent table. This inefficiency was spiking the costs on the data warehouse side, where we pay on a per query basis, making this a problem that needed to be fixed quickly!

After the team met, we decided the best course of action was to modify the Primary Key definition so that it existed on the parent. While the solution was clear, applying the change had immediate problems.

In PostgreSQL table partitioning, the parent and child Primary Keys must match. On a partition parent table, the Primary Key must include the partition key column, which created an inconsistency with the child we’d need to solve.

We wanted a composite Primary Key covering the id and created_at columns on the parent.

No problem, we’d just modify the Primary Keys for all tables, right? Unfortunately, this type of modification locks the table for writes, meaning we’d have an extended period of data loss if we missed writes, meaning this was not an acceptable solution. We’d need another option.

We didn’t want to take planned downtime, we did want to modify the Primary Key definition, and we knew the modification would take a long time to run.

How could we solve this problem?

Solution and Roll Out

This same table would need to be modified on about 10 production databases, ranging in size from small to large. For the smaller databases we modified the child and parent Primary Keys and could tolerate the lock duration for new writes.

For the large database, we could in fact tolerate the lock duration, so we went for the straightforward solution. We removed the existing child keys, and added the new key definition to the parent, which propagates to the children. However, for the big database we’d need a unique solution.

We iterated through various approaches, and settled on a series of tricks to achieve on online modification.

The strategy effectively “hid” the lock period by performing the modification while the table was disconnected from concurrent transactions.

To achieve this, we used a placeholder table that continued to receive writes and answer queries while the original table was being modified in the background.

For the placeholder table we cloned the original table. We swapped in the placeholder in a transaction with renames (ALTER TABLE ... RENAME TO) so that no writes would be lost.

The application would also read from this table as SELECT queries and a smaller amount of UPDATE queries.

We decided to duplicate some data into the placeholder so that it was available for the reads. We’d discard the placeholder after it was no longer needed.

To make the duplication fast, we used the COPY command, and combined that with incremental copies right at the end.

The command below will dump the content of the month’s data into a file.

\copy tbl_202305 TO '/tmp/tbl_202305_dump.csv' DELIMITER ',';

We can then load the data from that file into the placeholder table.

\copy tbl_placeholder FROM '/tmp/tbl_202305_dump.csv' DELIMITER ',';

This load should be done right before the swap operation. To fill in what’s missed, we layered in the additional incremental inserts based on the last copied row id. Starting from the max(id) in the placeholder, we can copy in any new rows that were missed using the SQL below.

INSERT INTO tbl_202305 SELECT FROM tbl WHERE id > 123; -- the max(id) after loading from the file

We could run the statement above, and then even run it one last time inside of a transaction, to make sure that no rows were missed.

While the placeholder table was standing in, the ALTER TABLE and ADD PRIMARY KEY (id, created_at) modification could run. Applying the Primary Key constraint to the parent table and all children, which ended up taking about 30 minutes, did not block any writes.

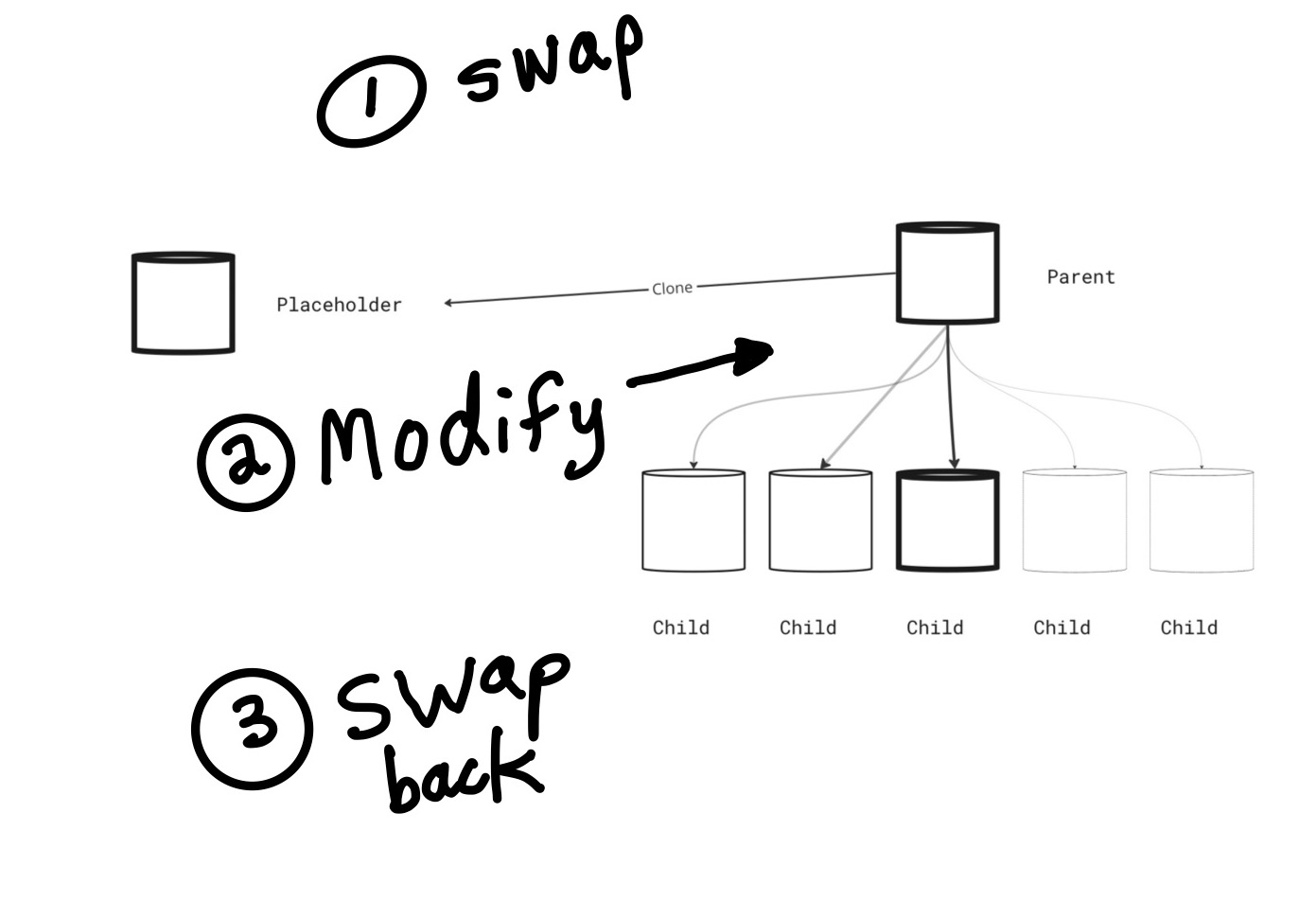

The diagram below shows the steps after the table was cloned and populated.

The sequence of steps are the first swap as step 1, modifications to the partitioned table as step 2, and then step 3 as a second fill and swap.

In the next section, we’ll share some of the SQL used to accomplish this.

The SQL

In the example below, tbl is the name of the table being modified. It has the columns id and created_at. The table was copied using INCLUDING ALL which includes extra objects like indexes but does not include data.

-- create an empty placeholder table

CREATE TABLE tbl_placeholder (LIKE tbl INCLUDING ALL);

-- swap tables around

BEGIN;

ALTER TABLE tbl RENAME TO tbl_offline;

ALTER TABLE tbl_placeholder RENAME TO tbl;

COMMIT;

-- Remove all the existing child-only primary key constraints

-- Repeat this for all children

ALTER TABLE tbl_202305 DROP CONSTRAINT tbl_202305_pkey;

-- Add the constraint now that the table is "offline"

-- This will propagate to all the children, which are also "offline"

ALTER TABLE tbl_offline ADD PRIMARY KEY (id, created_at);

-- Since we're also filling, perform a VACUUM on partitions

VACUUM ANALYZE tbl_202305;

-- Swap the tables a second time.

-- The "offline" table has been modified and is once again

-- ready to be put into duty

BEGIN;

ALTER TABLE tbl RENAME TO tbl_placeholder;

ALTER TABLE tbl_offline RENAME TO tbl;

COMMIT;

Wrap Up

In this post, we discussed a operational problem we encountered, where we determined we’d need to modify the PRIMARY KEY constraint on a large partitioned table.

Because this would lock and block concurrent transactions, we showed part of how we solved it using an online/zero downtime strategy. This strategy meant we’d avoid disrupting any other transactions, although the strategy was risky and required careful planning and execution.

Although this technique is not recommended for regular use, it was useful for emergency use to work around normal operational table locking from DDL modifications, that could otherwise cause data loss and errors.

By writing up and rehearsing the steps in advance, pairing and mobbing on solutions on the team, the engineering team was able to perform this operation online without errors.

Once the primary key modification was complete, the excessive data warehouse queries stopped. The data warehouse could again efficiently determine new and modified rows.

Thanks for reading this post!

If these kinds of engineering challenges interest you, please take a look at the Fountain Careers page for engineering positions and get in touch.